| Album notes by Rip Rense - 1996

|

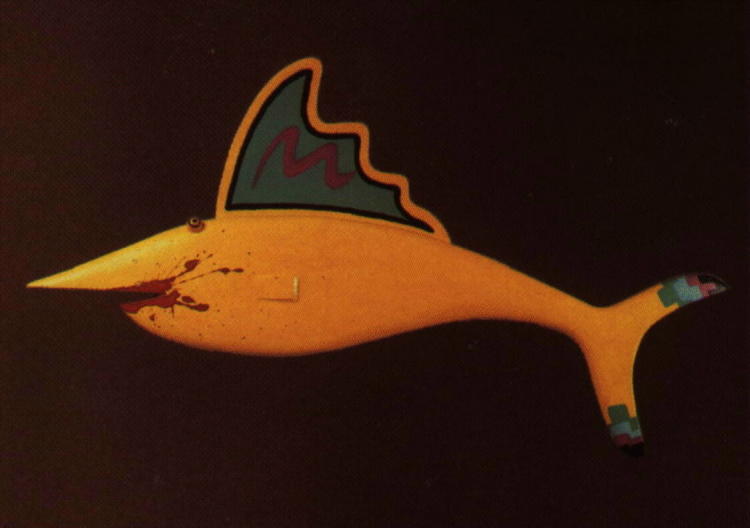

| It rested for years beside the fireplace of Frank Zappa’s basement / listening room - a large, yellow fiberglass fish with droplets of blood painted inexplicably around its mouth.

|

|

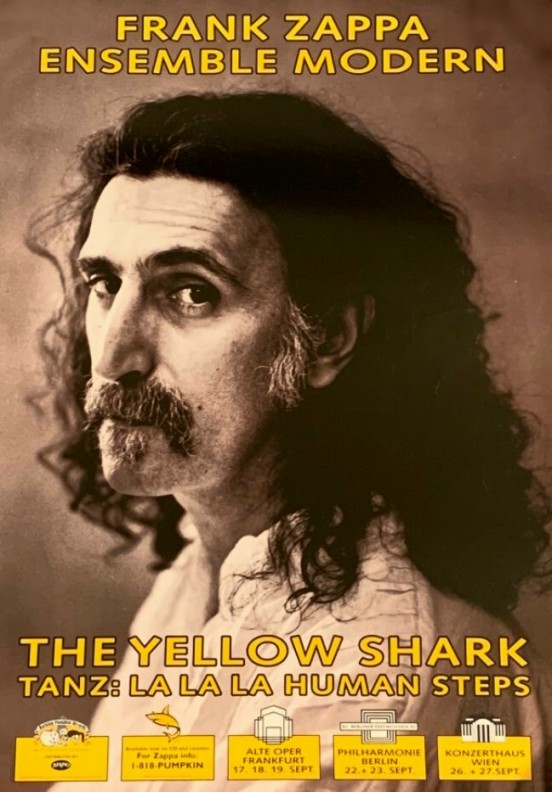

| Today it resides permanently in Germany, the enduring icon of one of Zappa’s most successful musical ventures, a series of concerts in September 1992, entitled “The yellow shark”.

|

| The story of how the fish got from Los Angeles to Europe is also the story of one of the most originally realized performances of new music in history. At least, that is, in the history of those magnificent but often conservative listening rooms known as “concert halls”.

|

| It begins with L.A. artist Mark Beam, a longtime Zappa appreciator who felt compelled to anonymously bestow upon the Zappa family a Christmas present in 1988. Carved out of a surfboard, Beam’s “kind of a mutant fish” arrived unannounced at the offices of Intercontinental Absurdities (Zappa HQ), and eventually found its way to Frank’s basement. A note inviting the owner to complete the piece of art by placing an item of choice into the fish’s bloody jaw was ignored.

|

| In the summer of 1991, one Andreas Mölich-Zebhauser, manager of the European contemporary music group, Ensemble Modern, sat in the basement with Zappa and EM conductor Peter Rundel, discussing the music the Ensemble had just commissioned from Frank for the 1992 Frankfurt Festival. Suddenly, Mölich-Zebhauser spied the fish. He took its sailfin for a dorsal.

|

| “When I saw the yellow shark” Mölich-Zebhauser recalled in English he apologized for “for me it was completely clear that it must become the symbol of our event, of our tour! Because the yellow shark, he’s so pregnant with some of Frank’s characteristics. He’s very hard and a little poison, but on the other hand he’s very friendly and charming. Two things which Frank can be very often: poison for bad people, charming for good ones! Of course, also it’s such a good logo”.

|

| Not realizing Mölich-Zebhauser’s bizarre plot, Zappa generously gave the “shark” to him, writing a “little deed” in order to get it past any suspicious customs agents. The deed read: “This is to confirm to whom it may concern that this yellow shark is Andreas Mölich-Zebhauser’s personal fish, and he can do with it whatever he wants. Frank Zappa”.

|

| “Andreas would drool over that object”, said Zappa “He loved it. The next thing I know, the whole project is being called ‘The Yellow Shark’, which he said sounds really good in German (‘Der Gelbe Hai’), and I said it sounds really dorky in English. People think the name of the music is ‘The Yellow Shark’. I said we’ll call the evening ‘The Yellow Shark’. What the fuck are you going to call it? Doesn’t make any difference”. (*) (It might as well be pointed out that there is aesthetic precedent for sharks in Zappa’s art, dating to 1971, when the Mothers of Invention brought undreamed fame to the lowly mud shark in a song of the same name).

|

| Although the title had nothing directly to do with the music, it will forever evoke memories of the first time Frank Zappa’s so-called “serious” (orchestral) work was rendered with a level of accuracy and dedication that both delighted the composer (rivaled, perhaps, only by Pierre Boulez’s Ensemble Intercontemporain, which commissioned and recorded a number of his works in 1984) and left audiences in Frankfurt, Berlin, and Vienna alternating between rapt attentiveness and ovation. The popular and critical approval, it should be added, persisted even when the composer was unable to attend or help conduct due to illness. (In Zappa’s 30 year plus history of working with orchestras ranging from the London to Los Angeles Philharmonics, numerous projects have been derailed or hampered by inadequate rehearsal time, stifling union restrictions, and politics ▲).

|

| Aside from being remarkable as an unusually precise (though, the composer cautions, “not 100% accurate”) rendition of Zappa’s orchestral and chamber music, “The Yellow Shark” was singular for several reasons. This was first time a group of classically trained musicians performed music in a manner technically similar to a large-scale rock concert. That is, the music was carefully amplified - not wantonly distorted, but meticulously expanded, mixed, and balanced (the players even had individual stage monitors). Each work was composed and/or arranged specifically for the six-channel sound system that Zappa engineers David Dondorf, Spencer Chrislu and Harry Andronis devised and intricately tailored for each concert hall. This sonic arrangement was as organic to the aesthetics of the music as any other part of the compositional process. Zappa actually “placed” instruments in desired six-channel configurations by sampling and mixing them in his home studio, the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen (UMRK), and the same mixes were re-created live. Finally, it is certainly a rather blue moon when a contemporary composer is invited to, and hired to, put together a program of his own music for such a sophisticated (technical and artistic) presentation, when bureaucracies and personalities from more than a dozen countries unite and cooperate over a nearly two-year period to bring about such a project.

|

| It took a musical group about as iconoclastic as Zappa himself to make it possible. Founded in 1980 under the management of the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie, the Frankfurt-based Ensemble Modern is about as improbable an item as, say, a yellow shark: a self-sustaining, self-determining group of 18 superbly trained players (with, in this instance, additional players of like virtuosity who regularly perform at least five or six times per year with the Ensemble) that survives by conceiving and executing programs devoted entirely to contemporary music. It does on a large-scale essentially what the Kronos Quartet does on a small one, but with a less pop-oriented repertory.

|

| The EM first sought to commission Zappa in early 1991 after German documentary filmmaker Henning Lohner - who had made Zappa the subject of one of his films - suggested to Dr. Dieter Rexroth, head of the Frankfurt Festival, that he solicit a major orchestral piece from the composer. When Zappa displayed little interest in a project of such sprawl, Rexroth, Karsten Witt and (his successor) Mölich-Zebhauser instead came up with the idea of commissioning new music for the EM. They flew to L.A. and introduced Zappa to the Ensemble via a CD containing pieces by Kurt Weill and Helmut Lachenmann. A deal was struck almost instantly.

|

| “I’m not even a massive Kurt Weill fan”, said Zappa “but what I heard on that CD really impressed me, just because of the attitude and the style and the intonation of the players. There were parallels in that music and the type of performance it was getting that I thought would be easily transposed to the some of the types of things that I write. I figured if they can play that and bring it off, then they should be able to handle my stuff. I could hear certain things that reminded me of the ‘Uncle Meat’ album. The other thing that impressed me was their recording of the Lachenmann piece, which is based on all of the noises you’re not supposed to make when you play an instrument - mistake noises. It’s a great piece”.

|

| The EM flew to L.A. at its own expense and spent two weeks rehearsing with the composer at his Joe’s Garage studio in July 1991. Ensemble members not only routinely arrived for work three or four hours early - just to practice - but they repeatedly asked for transcriptions of Zappa’s most “humanly-impossible-to-play” Synclavier pieces (and usually got them, as with “G-Spot tornado”). The composer drilled the group in his elaborate methods of improvisational conducting, and later recorded, or “sampled” each player’s range of sounds. By programming this array of samples into the Synclavier, Zappa was, in effect, able to compose by “playing” the Ensemble on the instrument, then edit and mold as was his penchant.

|

| Later, in a time-consuming and painstaking process, Zappa - along with composer / arranger / copyist Ali N. Askin, and UMRK jack-of-all-Synclavier-trades Todd Yvega - took voluminous printouts of raw numerical data representing finished Synclavier works, and translated them into written music. Askin, recommended for the job by longtime friend Mölich-Zebhauser, was subsequently asked by Zappa to create new arrangements of Zappa “standards” like “Dog breath” and “Uncle Meat” (combined here as “Dog / Meat”), “Be-bop tango”, “Pound for a brown”, and “The girl in the magnesium dress”. In July, ‘92, Zappa flew to Germany and spent an additional two weeks rehearsing with the EM (under memorable conditions; the staunch group sweated through long days in a poorly air-conditioned building at the height of a punishing heat wave).

|

| The ultimate result: a 90-minute program of 19 works including a piano duet, string quintets, and small ballets starring the La La La Human Steps dance ensemble (all but two of the works - an introductory improvisation, and “Amnerika” - appear on the CD). Stylistically, the often dauntingly polyrhythmic and polymetric pieces spanned the universe of Zappa influences - everything from Edgard Varèse and Anton Webern to “Louie Louie”.

|

| Quoth Ali N. Askin: “I think Frank’s music is unique in this way: I don’t know of any composer who is mixing or switching between all those influences and musical dialects he uses. Somehow he managed to work with these many, many influences since the very beginning in his musical career. And I think for many composers this would be a really big danger, to get lost in all those things you could do-like a child lost in a toy store. But he’s really original at using all these influences. I could compare him, in that regard, to somebody like Stravinsky. He is also influenced very much by European composers, but he doesn’t care about what comes after what. He uses the ♫ ‘Louie Louie’ progression and goes straight into a cluster which could be written by Ligeti, and he doesn’t care, as long as it sounds good. There is no ‘theory’ about what could be used, like ‘could I use a C-major chord in this 12-tone context?’, or something like that. The last judge is his ear. This fresh way to work with all those colors and textures, I think, is striking”.

|

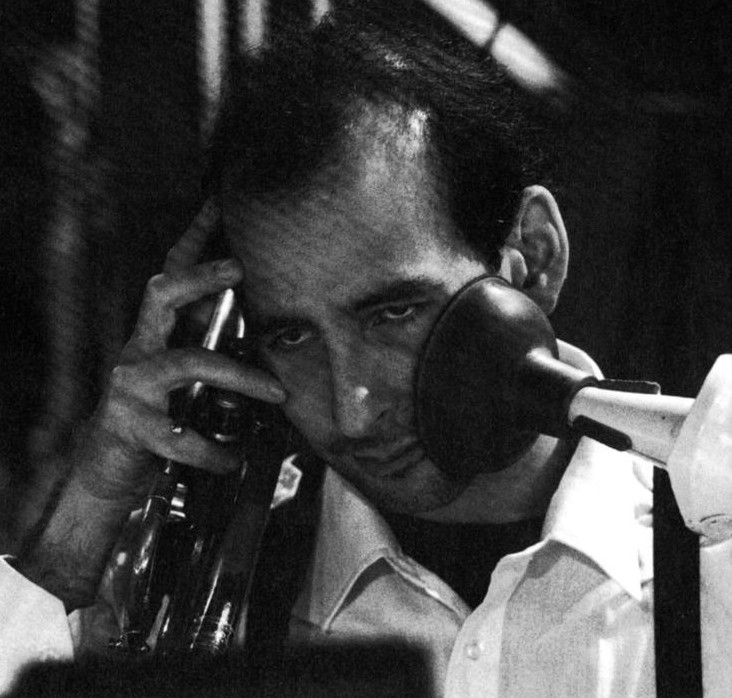

| Two more characteristics of Zappa’s approach to music perhaps bear mentioning. First, he has always been adept at bringing out “hidden talents” in his musicians. As Yvega put it: “If he’d hire a sax player who’s good at playing the sax, it would almost be redundant and pointless to have him just play the sax. Frank already knows he does that. But then he’ll find out that he can tap dance as well - and make use of that”. Accordingly, the players of the EM found themselves as actors and narrators - most spectacularly, in the cases of violist Hilary Sturt (who delivers the arresting recitative in “Food gathering in post-industrial America”) and Hermann Kretzschmar. Kretzschmar, who normally is employed at the piano, cembalo, and celeste, found himself inside a piano at Joe’s Garage rehearsals, reciting everything from his library card ▲ to a rather colorful letter-to-the-editor of a flesh-piercing magazine ▲ (detailing methods of impaling genitals) while the Ensemble gamely improvised under Zappa’s direction. At the “Yellow Shark” concerts, Kretzschmar’s Dr. Strangelove like vocalizing was employed to recite (verbatim) actual questions from a less-than-hospitable U.S. customs form during “Welcome to the United States”.

|

| This points up another of Zappa’s characteristic compositional traits: he is open to chance and whimsy in choosing subjects and themes, whether in music or text. He often makes artistic use of whatever happens along (hence the customs form, piercing magazine, and library card) a concept he labels “Anything Anytime Anyplace For No Reason At All” (AAAFNRAA). If this seems far removed from more “lofty” (and sometimes condescending) artistic sensibility, well, it is. As Yvega, who is also a composer, commented: “A lot of times in the world of so-called serious music, people take it so seriously. To Frank, everything is entertainment. You’re either entertained, or you’re not. And nothing is serious.Which is why you can have something that supposedly is serious and suddenly have someone stick his plunger on the side of his face.

|

|

| I do think of his music as being important in the sense I think it will be around for many centuries. It’s serious in that respect, but it is, after all, there to amuse us”.

|

| Many composers - Ives, Stravinsky, Mahler, for obvious example - have quoted wildly disparate music, and employed highly varied musical styles, in their work. It is probably fair to say that no one has ever done it to Zappa’s extent.

|

| “We have been quite surprised by this” said Mölich-Zebhauser. “For example, the string quartet (‘None of the above’), or the woodwind and brass quintet (‘Times Beach II and III’) are pieces on a very, very high level, also compared with very strict European composer’s school. For me, what is really important is that a piece like the ‘None of the above’ string quartet has a level like some of the classics of the 20th century - Webern pieces, and things like that. Really. With such pieces, Frank demonstrates he has the capacity to do a good job also in this metier, but you must imagine in the ‘Yellow Shark’ evening, there were at least three or four music styles: new arrangements of old music of his, some contemporary pieces, some jokes, the electronics, and the jazz element. And the crowning thing for me was how it fit together; that it is possible to give one evening with four or five different music styles, and nobody says: ‘Oh my God, what’s happening now - oh, forget it’. It seems to be (due to) the personality of Frank that this can work”.

|

| Conductor Rundel goes a step farther. Certainly, he allows, other composers are capable of writing music in diverse veins, although not as diverse as Zappa without bordering on dilettantism. What additionally sets Zappa apart is that his musical personality is unmistakable in any context: “I think you can hear” he said “If you listen to his music not knowing who wrote it, that it is Frank Zappa. It’s especially in the way his melodies are built; they are very, very personal and typical of him. You don’t have to make a distinction between him as a guitar improviser and as a composer, it’s still Frank Zappa! You can hear it. That’s astonishing, because the styles are so different”.

|

| If there’s a thread running through all Zappa’s music, aside from distinctive melodic or rhythmic signature, Rundel believes it’s the self-taught composer’s penchant for rules-breaking them.

|

| “You know, so-called contemporary classical music, and also rock music and jazz music all have their rules” he said. “Frank, you know, doesn’t like rules so much, and the reason is that they actually are boring to him. His music in its best parts is free music, because he doesn’t follow the rules. And I think that’s very refreshing - to listen to music which has the courage also to question itself. And question the traditional listener”.

|

| It also questions the non-traditional listener. About half of the opening “Yellow Shark” crowds “came to see Frank” according to Mölich-Zebhauser, yet they left the concerts “loving the music”. And Zappa, at one point, happily mentioned that “we even had a bunch of 70-year-olds out there getting off on it”. Thus, “The Yellow Shark” seems to have introduced many to the pleasures of new music, and to have taken a small bite out of audience conservatism in the process.

|

| “I think what was very important” observed Askin “was that Frank has this power to put modern music, or new music, in front of such a big audience and into the minds of many people who have never heard about it. To be able to listen to such complicated music like ‘G-spot tornado’ and ‘Get whitey’ and ‘Amnerika’ (not on the CD), well, it was a very good advertisement for new music - without synthesizers, without electric guitars - just good music played by good musicians”.

|

| Zappa walked out onstage at the Frankfurt Alte Oper 17 and 19 September 1992, and was greeted by stunning applause (“There was such a noise” said Mölich-Zebhauser “you can’t believe it”). He acted as emcee, and conducted three pieces in those two concerts: “Food gathering in post-industrial America, 1992”, “Welcome to the United States” and the encore, “G-spot tornado”. Critics (notably a particularly tough Dutch writer) praised the music - as well as performances in Berlin (22, 23 September) and Vienna (26, 27, 28 September) - effusively. The composer was plainly thrilled: “I’ve never had such an accurate performance at any time for the kind of music that I do” he said, shortly after returning from the event. “The dedication of the group to playing it right and putting the ‘eyebrows’ ▶ (Zappa-ese for extra-musical attitude) on it is something that would take your breath away. You would have to have seen how grueling the rehearsals were, and how meticulous the conductor, Peter Rundel, was in getting all the details worked out”.

|

| “You know what normally happens at a modern music concert” he continued “If you have an audience of 500, it’s a success. And (here) you’re talking about averaging 2,000 seats a night, and massive, lengthy (twenty-minute) encore-demanding applause at the end of the shows. Stunned expressions on the faces of the musicians, the concert organizers, the managers, everybody sitting there with their jaws on the floor. And I didn’t have to stand there and be Mr. Carnival Barker to draw ‘em in”.

|

| Indeed, Mölich-Zebhauser expected to lose half the audiences after Zappa went home. Instead, the attendance and approval held fast. “And I think that’s a pleasure for Frank” the EM manager said “because he was never interested with this project being… the big star organizing the orgasm of half the audience. He didn’t want to be the hero of the concert. He wanted to have his music, and this worked”.

|

| One of “The Yellow Shark”’s most indelible moments, in the views of Mölich-Zebhauser and Askin, came when Zappa conducted the frenetic encore, “G-spot tornado”, while the La La La Human Steps whirled about him.

|

|

| Despite the impact of that scene, Askin was even more impressed with how the audience was listening to the really hard stuff, like the “Times Beach” quintet, and also to “Ruth is sleeping”. “This was” he said “fantastic - how the audience reacted, how they listened, and how quiet they were; it rarely happens like that”.

|

| Zappa does not consider himself a conductor (although he did guest-conduct Edgard Varèse’s ♫ “Ionisation” at the 1983 Varèse Centennial Concert in San Francisco, and his own Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Symphony Orchestra in Los Angeles in 1977). In fact, his conducting is really something other than conducting. While he does beat time and cue instruments when necessary, his preferred podium task is actually the creation of spontaneous music with his lexicon of inimitable body and sign language. This system has been a constant throughout his career, although it is likely that the EM learned it in greater detail and subtlety than any other Zappa-led musicians. Aside from eliciting an enormous array of improvised sounds, Zappa-as-conductor is also able to trigger prearranged “clusters” (learned passages) according to whim. In effect, an ensemble truly becomes an instrument, and the conductor the soloist.

|

| The results of this technique are sometimes hilariously in evidence in both “Food gathering in post-industrial America” and “Welcome to the United States”. Askin commented: “In the video (opening night was broadcast live over pay-per-view German television) you can see what Frank’s face was like. You see how he was laughing and conducting and making little gestures to the musicians. I have never seen somebody conduct like that. He says of himself, he’s not a real conductor - which he isn’t. But nobody is able to lead a group of musicians like he does. It’s unbelievable. His little finger talks more than any big conducting movements of Karajan, I think! Just look at him when he’s smoking. That tells a story”.

|

| There is another story to be told about “The Yellow Shark” and it is that of indefatigable UMRK audio specialists Chrislu, Dondorf and Andronis. It is a story so technical as to likely be intelligible mostly to technicians. Suffice to say that their work essentially formed the “Sharks” spine. Here’s a layman’s explanation from Dondorf: “We had to design a system that would take into account the unique needs of the compositions, the configuration of the venues, the monitoring needs of the artists, the requirements of 48 channel digital audio recording as well as multi-camera live broadcast video. Frank envisioned something new, somewhere between a rock show and classical concert, where the audience sat surrounded by six loudspeaker locations, the sound from each of these points being different mixes as determined by the score, each audience member hearing the show from a unique audio perspective. Everything we were doing was new: the music was written for a six-channel sound system which hadn’t been built, put together or operated, and it was going to be played back this way in halls that weren’t built for it”. (Or, as Andronis said to Zappa when first approached: “A 26-piece orchestra, performing in some of the finest concert halls in Europe, mixed live in six-channel surround? Uh-huh”).

|

| Add to this the fact that they were working with a Dutch TV crew, a French company in the recording truck, a German company providing the public address gear - to say nothing of musicians from Germany, England, Australia, and New Zealand - and, as Chrislu put it: “For that to be pulled off, in and of itself, without anyone shooting anyone, was quite miraculous”.

|

| In non-technical terms, just how was this six-channel miracle discernible in concert? Zappa gave an example: “In the case of the string quintet, the instruments surround the audience, and you get to hear the counterpoint in a way that you’ve never heard before. It’s not that it’s loud, that it’s blowing people away, it’s clear and the musical detail is in your face. The sound of the instruments has not been electronically tweezed in any way. It’s a hi-fi experience to the nth degree”.

|

| A final aspect of all the techno sleight-of-hand merits a word. The performances on the CD - as is the case with most Zappa CDs - are composites of “best” performances from different concerts melded together by the composer. (“And when you listen to the CD” notes Chrislu “it’s quite amazing we were able to pull it off. The way it all fell together, Frank was able to make some very suave edits. You really can’t hear the ambience change”).

|

| The Yellow Shark himself (gender has apparently been established by Mölich-Zebhauser, who refers to the creature only in the masculine) made only one appearance in the concerts - at the beginning of each program, “swimming” across the stage in the hands of a stage manager. Today, he is proudly mounted in the home of the EM manager, awaiting a return to the stage only if the project happens to be realized in the west (in that event, Mölich-Zebhauser advises, in order to allay Zappa’s distaste for the title: “We can use the German name, ‘Der Gelbe Hai’”).

|

| But there is a little more to this fish story; this one Zappa orchestral venture that didn’t get away. It seems that artist Beam, the creator of the shark, got wind of the fact that the beast had gone to Germany and changed its name. He was nonetheless delighted that the pairing of his gift with Frank Zappa had yielded such a saga of results: “That’s a lot of what I do” said Beam “put two things together that don’t belong, and get an element of surprise out of it. ‘The Yellow Shark’ seemed to work out well”.

|

| So well, in fact, that as of this writing, leaning next to the fireplace of Zappa’s basement / listening room is a fiberglass representation of a sea animal of the same size and shape as the Yellow Shark - except that it is entirely covered with a thick black-and-white fur-like coat, like a holstein. Beam calls it “The Cow Shark”.

|

| “We’ll see what happens” he said.

|

|

| (*) It does, apparently, in Japanese. According to Simon Prentis, who has the peculiar task of translating Zappa lyrics into Japanese for release in that country, there is a misconception in Japan that yellow shark is actually some mysterious codified description of Japanese economic aggression. Not true.

|

|

|

| [Rainer Römer] Ladies and gentlemen, here he goes, Peter Rundel, he seems to be disgusted. Whatever.

|

| RIDERÒ, RIDERÀ!

|

| HEUTE FÄNGT DIE FASTNACHT

|

| HA HA HA!

|

|

|

| LAUGH NOW!

|

| HA HA HA HA HA!

|

|

|

| Be quiet!

|

| Von seiner Werkbank zu uns heute Abend hergekommen ist unser Hermann Kretzschmar. Wolle mer’n reinlasse?

|

|

|

| Laugh now!

|

| Ha ha ha ha ha!

|

|

| [Hermann Kretzschmar] Welcome to the United States

|

|

|

| This form must be completed by every nonimmigrant visitor not in possession of a visitor’s visa

|

|

|

| Type or print legibly in pen in ALL CAPITAL LETTERS

|

|

|

| USE… ENGLISH!

|

|

|

| Item 7: if you are entering the United States by land, enter “LAND” in this space (LAND!)

|

| If you are entering the United States by ship, enter… uh-uh, “SEA” in this space

|

|

|

| Do any of the following apply to you? ANSWER “YES” OR “NO”! (NO! NO! YES! NO! YES! NO!)

|

|

|

| A. Do you have a communicable disease (COUGH NOW!); physical or mental disorder; or are you a drug abuser or addict?

|

| Tell me, Bill: “Yes” or “No”. (No) Louder. (No!)

|

|

|

| B. Have you ever been arrested or convicted for offense or crime involving MORAL TURPITUDE or a violation related to a controlled substance; or ever been arrested or convicted for two or more offenses for which the aggregate sentence to confinement was five years or more?

|

| Answer “Yes” or “No”. (Yes! Yes, sir! Yes! No! No! No!)

|

|

|

| Or been a controlled substance trafficker; or are you seeking entry to engage in criminal or immoral activities?

|

| Answer “Yes” or “No”. (Yes or No)

|

| Thank you!

|

|

|

| C. Have you ever been or are you NOW involved in… espionage… or… sabotage; or terrorist activities; or genocide; or between 1933 and 1945 were YOU involved, in any way, in persecutions associated with Nazi Germany or its allies?

|

| Answer “Yes” or “No”. (Yes)

|

|

|

| THANK YOU VERY MUCH! AND WELCOME TO THE UNITED STATES!

|

|

|

| [Rainer Römer] Thank you very much! Here they go! Frank Zappa and Hermann Kretzschmar!

|

|

|

| Back on stage, Peter Rundel!

|

Photo by Fritz Brinckmann.jpg)

.jpg)

Photo by Fritz Brinckmann.jpg)

.jpg)